A word or two before the book review:

You’ve certainly heard about the secretly taped conversation with Mrs. Alito, the wife of one of the Supreme Court Justices. In that conversation she reveals the revulsion she feels each time she sees a Pride Flag.

She is so repulsed by the Pride Flag that she dreams of making a flag of her own design and flying it in some sort of an act of revenge.

“I made a flag in my head,” she’s quoted as saying. “This is how I satisfy myself. I made a flag. It’s white and it has yellow and orange flames around it. And in the middle is the word ‘vergogna’. Vergogna in Italian means shame. Shame, shame, shame on you.”

Mrs. Alito’s response to the Pride Flag is exactly why the Pride Flag exists. For years in this country LGBTQ people were made to feel shame just for being who they are. Shunned by friends and family, ostracized from their jobs, most gay people lived in fear and hiding -”in the closet” as we used to say. They were shamed by society, and thus many in turn felt ashamed - exactly what folks like Mrs. Alito would like gay and trans people to feel right now, today.

But some brave queer folks knew that the problem was not with themselves, not with what nature had made in them, but with how society reacted. They were proud to be who they were, and they fought against society’s repression. Through their efforts LGBTQ people have come out of the closet and I’m not sorry to say that we are not going back in.

If you’d like to know more about the rainbow Pride Flag, and how it came about, check out this piece from the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco.

The Transgender Flag, often seen flying alongside the Pride Flag, has its own history, covered here by Point of Pride, a 501(c)(3) charity providing assistance to transfolk.

Happy Pride Month to all, and on to the book review…

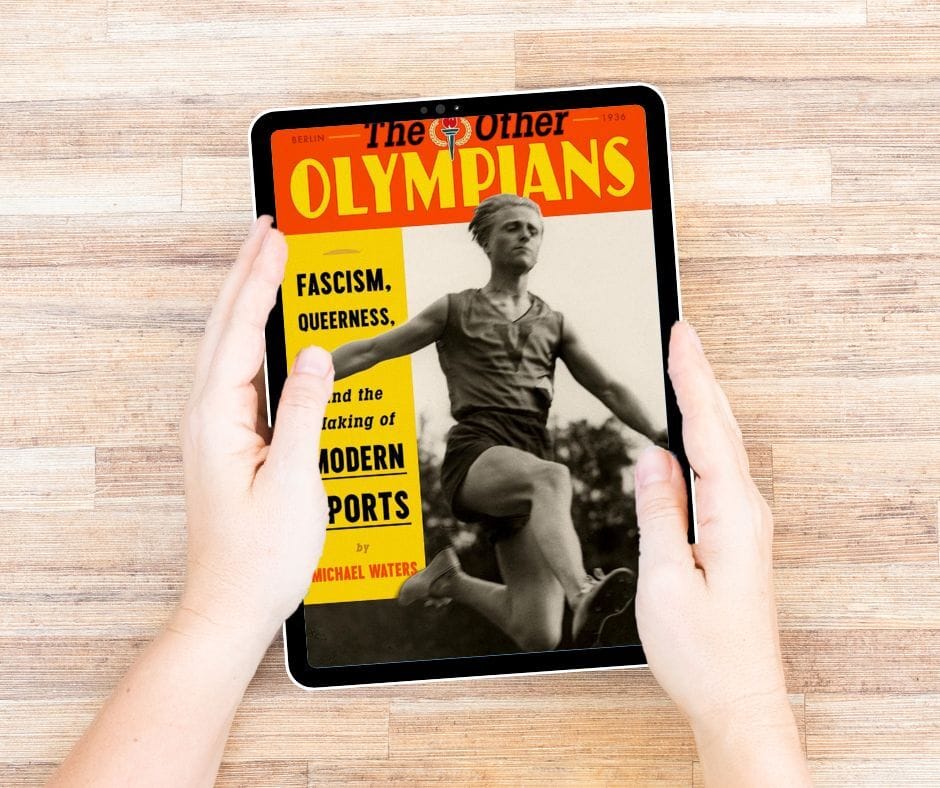

Journalist and freelance writer Michael Waters has written a fascinating history of transitioning athletes of the early twentieth century and how the Olympics organization of the time reacted to them. The book covers events that were new to me, and it shines a light on the background to an issue that today manages to provide fodder for political controversy.

Waters follows most closely the life of Zdeněk Koubek, a Czech track athlete. Koubek won five national titles and two medals at the 1934 Women’s World Games and was considered one of the best athletes in Czechoslovakia. Koubek was always shy around other athletes, and never changed or showered in communal locker rooms. This, along with some of Koubek’s physical characteristics (the athlete was said to have a need to regularly shave off facial hair) prompted rumors about whether Koubek was a woman or a man.

In 1935 Koubek withdrew from sports and after a period of time announced that he would live the rest of his life as a man. He consulted with physicians, underwent examinations, and was determined to have predominantly male sexual characteristics. He underwent some type of surgery (what exactly is not known today) and by 1936 was pronounced by his doctors to have “become” a man.

The press and public reaction to Koubek and his transition was curious but generally positive. Around the same time that he transitioned, another athlete who had previously competed in the Women’s World Games came out and transitioned as a man. The British athlete known as Mary Louise Edith Weston became Mark Weston. Again, public and press expressed curiosity but were generally positive.

Author Michael Waters (photo source: www.michaelwaters.com/about)

Waters emphasizes that it is difficult to put the labels we use today on these athletes. Whether they were intersex (being born with biological traits that do not fit traditional classifications of male or female) or trans (a person whose gender identity doesn’t match that typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth) isn’t really known, as those terms were not used in the 1930s. How reporters and the general public processed what was happening to these athletes would not take such distinctions into account.

Waters makes the case that leading theories of sex and gender at the time even contemplated the possibility that people could spontaneously experience a change in gender as a natural occurrence beyond their control. That’s quite a different understanding of sex and gender than we have today.

The other important person Waters follows in his book is Alice Milliat, the pioneering French female sports organizer who founded the Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale (International Women’s Sports Federation) and the Women’s World Games. She took these actions after the Olympics organizers refused to include women’s track and field events in the 1924 Olympics.

Milliat’s struggles with the Olympic organizers continued for several years after the 1924 games, up to and through the Berlin Olympics held in 1936. In general, as Waters’ research tells us, a powerful clique within the Olympic organizers (including the American Avery Brundage) did not want women competing in the Olympics track events, nor did they appreciate the competition that Milliat’s Federation and her Games represented. They worked hard to push Milliat to turn over her organization to them. She eventually gave in and did so after the 1936 games. As you might expect, women’s participation in the Olympics did not substantially increase until the 1970s.

Among the things that Brundage and his fellows did to push Milliat was to question how she could have allowed athletes to compete in her games when they did not display what they felt were “normal” female characteristics (referring to Koubek and Weston). Brundage proposed to the head of the Olympics that it begin instituting a policy of medical examination of women athletes before competing in the Olympics.

The policy became effective for women track and field athletes at the 1936 Olympics. Waters goes into detail about how many of the proponents of the testing instituted at the 1936 Games were the Nazi hosts, as it fit into their own notions of purity and “normative gender standards”. This included the Nazi sports doctor Wilhelm Knoll, who was one of the first to advocate for testing.

This notion that women athletes need to prove that they fit into what have never been well-defined criteria of femaleness persists to this day. Waters devotes several pages in this book to just how unworkable and unscientific such a pursuit actually is. The panic that some man will attempt to compete as a woman and ruin things for all the “real” women (or worse), is in the air these days, and is being exploited for political gain.

Interestingly, when Alice Milliat was questioned about whether Koubek’s medals should be revoked after he transitioned, she gave what I think was a brilliant reply. “If it is proved that [Koubek] has become a man,” she said, “it is logical to consider that previously she was a woman.”

RATING: Four Stars ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

RATING COMMENTS: A fascinating account of female to male transitioning athletes in the 1930s and how the Olympics organizers responded to them.

WHERE I GOT MY COPY: I read an advanced review copy provided through NetGalley and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the book’s publisher.

See What Others Think

Paul Duff’s Reviews: For me, this slice of history feels VERY current.

Title: The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports

Author: Michael Waters

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux (an imprint of MacMillian Publishers)

Publish Date: June 4, 2024

ISBN-13: 9780374609818

Publisher’s List Price: $30.00 (US hardcover. Price as of June 19 2024.)